Introduction

The paper focuses on the speaking component of the ESP course because of its relevance to the students’ needs. The students need English at the undergraduate level for campus placement (interviews and group discussions), for paper presentations, project presentations, for the workplace, and for higher studies. The University offers three English courses for its affiliated colleges at the undergraduate level considering the needs of the students: Technical English I for Semester I, Technical English II for Semester II, and Communication Skills Lab for Semester V or VI. Both Technical English I & II are four-credit courses, and Communication Skills Lab is a two-credit course. In all, English has 10 credits forming an important constituent in deciding the cumulative grade point average of a student. In the initial stages of the ESP course, a structural syllabus was followed concentrating on form. It gave way to a functional syllabus that emphasized language use, and gradually moved on to discourse analysis that stressed meaning, and later on, a skills-approach was adopted (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987). The Technical English courses in this study are skills-based and designed as English for Specific Purposes (ESP) with the aim of enhancing the English Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing (LSRW) skills. The syllabi follow an integrated skills-based approach giving equal importance to all four skills. In spite of the fact that speaking is a crucial component of the syllabi, it has been neglected by the teaching-learning community for several reasons. The topic undertaken for the present study is the Anna University syllabi of Technical English I and II (Regulation 2013) prescribed for first-year Bachelor of Engineering (B. E) and Bachelor of Technology (B. Tech) students of the academic year 2015-2016 in Semester I & II. The syllabi of Technical English I and II are given in Appendix 1. The focus of the investigation is the speaking-skills component of the syllabi.

The study investigates the teaching-learning context in the English-language classroom, and focuses on the following research questions:

- To what extent were the speaking activities prescribed for the engineering colleges affiliated to Anna University conducted in the English classroom?

- How effectively can speaking skills be imparted to the students?

The Speaking Skill in the ESP Classroom

In ESP courses, importance has been given to writing over speaking as written genres were considered essential to professional success in the past. Similarly, research in ESP is more focused on writing than speaking because of the relative ease in collecting and compiling written data (Feak, 2013). In ESP and EAP, the skills approach became central to its courses as skills and subskills were easily identifiable and teachable (Hyland, 2006; Woodrow, 2018). A skills-based approach has been used to help learners develop their speaking skills (Basturkmen, 2016). Even though the syllabus in the present study follows a skills-centered model, it has structural, functional, and discourse elements in it as mentioned by Hutchinson and Waters (1987). Dudley-Evans and St John (1998) also advocate an integrated skills approach for ESP learners. Unfortunately, speaking is neglected in the above-mentioned setting at the teaching level because only writing, reading, and grammar are tested during the end of semester examinations.

Speaking skills need to be given their due importance in the ESP curriculum. Hyland and Wong (2019) assert that the ability to communicate in English is necessary for the academic and professional success of the 1.5 billion people who are learning the language. Basturkmen (2016) argues that the ability to communicate in and follow academic discussion and spoken interchanges is seen as a critical skill for academic success. Difficulty for learners to speak in English has been noted in all early research in ESP and EAP (Jordan, 1997). Feak (2013) states the areas of inquiry with regard to research in speaking are: speaking in academic and professional settings, university lectures, classroom discussion, oral presentations, and conference-presentations.

An evaluation of the syllabus, the teaching-learning process, and the feedback of students’ perceptions has to be done periodically. In an ideal setting, Anthony (2018) argues that administrators and instructors can work together to build up the four pillars of the ESP approach; that is, needs analysis, learning objectives, materials and methods, and evaluation. Lockwood (2019) states that the work of the ESP Business-English syllabus developer includes various roles such as consultant, researcher, designer, deliverer, assessor and especially that of a program evaluator. Gaffas (2019) recommends that teachers take into account students’ views while analyzing and designing courses. Arnó-Macià et al., (2020) assert that it is a necessity to reassess the existing ESP courses and find out how far they have been adapted to the ever-changing needs of the engineering graduates in a globalized world. The results of the study show that needs analysis helps to re-evaluate ESP courses.

A considerable amount of research has gone into the study of the spoken language in the areas of ELT, Applied Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition. Byrne (1986) states that speaking is the ability to express oneself intelligibly, reasonably, accurately and without much hesitation. Most of the scholars agree that speaking is a complex phenomenon as it is a ‘real time’ phenomenon, and a medium that enables the learning of a language (Bygate, 1987). The difficulty in teaching speaking is because ESP and ELT practitioners may not focus too much on research in the area and hence tend to neglect it in the classroom. The three aspects of theory of speaking that need the attention of the practitioners are: the characteristics of spoken language, function of speaking, and the notion of acceptability (Brown & Yule, 1983; Luoma, 2004; Richards, 2008). Very often teachers find second language speakers using textually perfect sentences, when it is also acceptable to have incomplete sentences in spoken English (Brown & Yule, 1983). Therefore, it is the responsibility of the teacher to make the students aware of the characteristics of the spoken language and its differences from written language, so that the students would be more confident (refer to Brown & Yule (1983) and Luoma (2004)). The teacher should be in a position to make the students comprehend the functions of the spoken language—(1) Talk as interaction; (2) Talk as transaction (Brown & Yule, 1983), and (3) Talk as performance (Richards, 2008),—and design activities based on it, so that they would be more comfortable in using the spoken language, thus reducing their anxiety level. Making the learners aware of the different varieties of English and the notion of acceptability is also the responsibility of the teacher so that they can take pride in using their own variety of English. As Sun (2016) puts it, the English spoken by the native speaker was considered the norm in the past, but now the English spoken by speakers of other languages is being accepted, and English has emerged as an International language -- EIL. Charles & Pecorari (2016) describe the variation between spoken and written academic discourse using Biber’s (2006) multidimensional analysis (MDA). Corpus-based studies in academic spoken and written English as a lingua franca (ELF) explored English as a contemporary lingua franca, influencing and being influenced by other languages (Mauranen, 2019). Woodrow (2018) adds that such studies have done much to enhance the understanding of spoken English, particularly in academic settings.

The Study in Action

The study adopts a practical action research with two objectives: (1) The action goal -- to probe into the teaching-learning process, the methodology adopted, and the challenges and problems faced therein, and (2) The research goal—to evaluate the effectiveness of the methodology, and enhance the learners’ speaking skills by bringing about a change in the existing teaching-learning scenario.

The participants of the study were 605 first-year B. E / B. Tech students of the academic year 2015-2016 from 50 engineering colleges affiliated to Anna University, Chennai. They had all undergone the same syllabi of Technical English I and II in Semester I and II respectively. The study was carried out after their second semester because by then they were in a position to evaluate the two courses. The major research tools used consisted of data collected from two sources: (1) The questionnaire for the students, given in Appendix 2, and (2) The focus group interviews with the students, given in Appendix 3. Five focus group interviews were conducted after analyzing the responses of the students to the questionnaires for further clarification.

Data interpretation of the students’ survey and the research findings

The questionnaire for the Students’ Survey includes details regarding the students’ interpretation of the activities conducted in the classroom, the methodology adopted in teaching, the effectiveness of the teaching-learning process, the difficulties and challenges faced while developing the speaking skills, and their attitude towards teaching and learning.

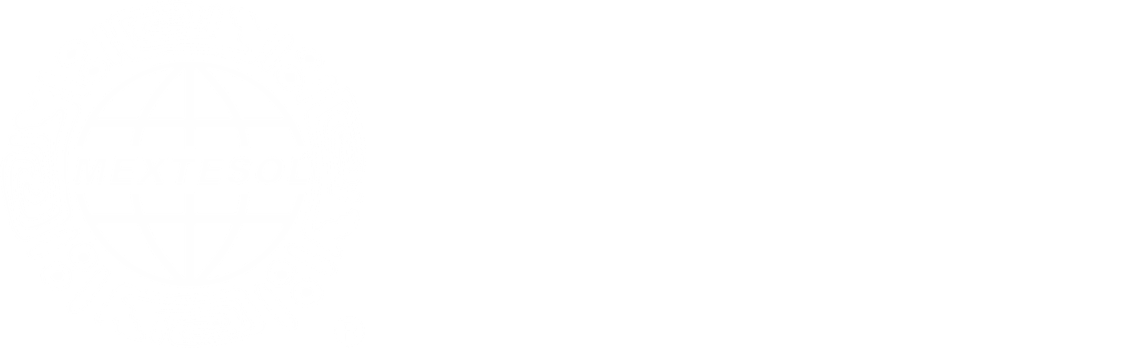

The following chart depicts the students’ response to the questionnaire:

Figure 1: The students’ response to the questionnaire

As shown in Figure 1, 77.7% agree that their expectations were met, but 22.3% did not agree. 77.4% were able to speak in English during the activities while 22.6% could not. Thirty three percent admitted that no other speaking activities were conducted besides the ones prescribed in the syllabus, while for 67%, debates, seminars, and language games and newspaper activities were conducted. Also, 77.9% stated that there was a purpose behind every speaking activity while 22.1% failed to understand the purpose; 73.2% found the speaking activities interesting while 26.8% did not, and 52.2% were divided into groups for the speaking activities while 47.8 % were not. For 59.8%, their teachers participated in the activities, for 40.2%, their teachers did not, while 71.1% understood the activities and cooperated with the teacher, 28.9% did not; 58.5% participated actively and helped their classmates to participate while 41.5% had difficulties; 67.8% agreed that they had learned how to speak in English from their classmates whereas 32.2% did not agree. According to the students 67.1% got equal opportunities to speak in English during the activities while 32.9% were deprived of the same; 75.7% got help from their teachers when they had difficulties in speaking while 24.3% did not. Also 76.5% agreed that their teacher’s attitude was positive towards them and their peers during the activities whereas 23.5% did not; 83% agree that their teachers corrected their mistakes and that of peers while 16.9% did not, and 78.5% admitted that their teachers were kind enough to wait for them to answer whereas 21.5% did not. While 76.5% stated that the advantage of taking part in the activities is to gain confidence in handling real-life situation, for 22.3% it is to help them to succeed at job interviews and for 1.2% it is beneficial for higher studies. For 73.9%, the greatest challenge faced is the anxiety of committing mistakes while for 26.1% fluency is the greatest challenge; 65.8% suggested providing them with equal opportunities inside the classroom to speak, whereas 21.8% put forward activities outside the classroom; 7.6% wanted opportunities to interact with their classmates; and 4.8% did not have any suggestions.

For a comprehensive view, the data interpretation of the Students’ Survey is sub-divided into: (1) The learners’ background and their comprehension of Spoken English, (2) The learners’ participation in the speaking activities, (3) The learners’ problems with the speaking activities, and (4) The learners’ expectations of their teachers and teaching.

The Learners’ Background and their Comprehension of Spoken English

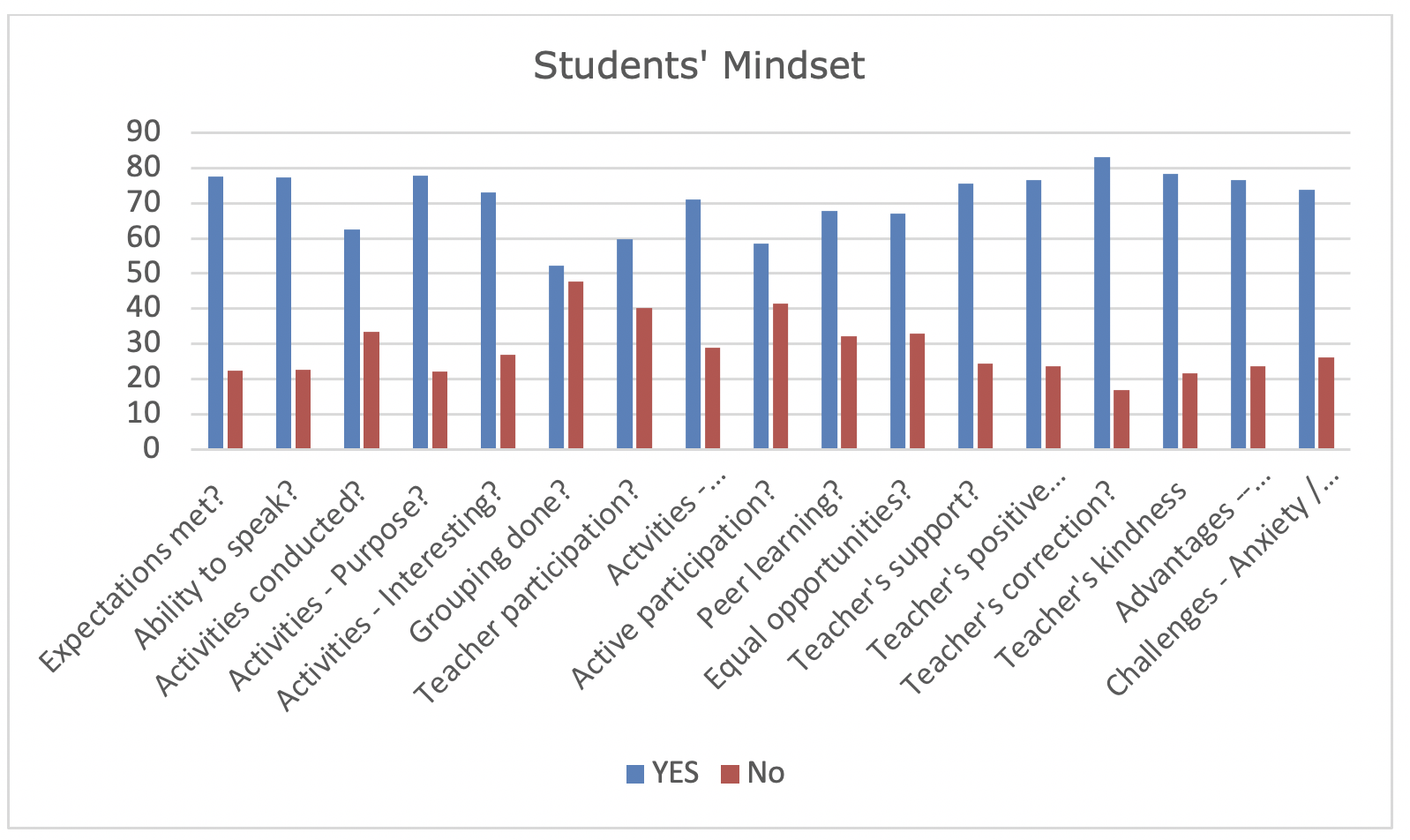

The following chart depicts the learners’ background:

Figure 2: Learners’ background

Figure 2: Learners’ background

As per the survey conducted, 60.5% are male and 39.5% were female students. As the learners’ belief system is largely determined by their social background, out of the total number of students who participated in the study, 34.4% were from the urban region, 43.3% semi-urban region, and 22.3% the rural region. The rural students found learning English very difficult in comparison to their mother tongue. Though these students were less than one-fourth of the total in most of the classes, their presence was notable because they had had hardly any exposure to English and suffered from a lack of comprehension and an inability to cope with the academic classes as the researchers observed in the classroom. Similarly, the difference between the learners of the urban and semi-urban regions was also perceptible but it could be bridged to an extent.

In addition to Hindi and English, 22 official languages are spoken in India. In the present survey, out of the 605 students, 31.7% completed their higher secondary school education in government schools where the medium of instruction was in their mother tongue, while 68.3% were educated in private schools where English was the medium of instruction. There was a vast difference between the students educated in government schools and private schools because the students from most of the private schools were used to speaking activities in English. Though the government-school students showed a keen interest in learning English, and desire to participate actively, they found it difficult to speak English grammatically. Naturally, when the faculty in the college expects them to participate in the speaking activities, it appears totally strange to them and they are distanced from their comfort zone. On the other hand, the private school students have a comprehension level in English almost as good as that in their native tongue, and they are also aware of their competence.

To find out the students’ motivational level in learning English and their attitude to Speaking, they were asked two questions. The responses showed they had different aims. Almost half of the students considered wanting a job as the driving motivation to learn technical English, while one-third learn English with the aim of getting good grades in the examinations, and over 20% learn for entertainment. The urban and semi-urban students were motivated to get a job while the students from the rural regions merely hoped to pass the examination, though getting a job is also very much in their minds. The students varied in their priorities regarding language skills, too: 62.1% considered speaking the most important skill, 30.7%, listening, 6%, reading, and 1.2%, writing. In spite of the fact that the teachers and students considered that speaking was the most important skill, very little effort was taken to improve it on a conscious level because of the resistance of the students. Often, the students were reluctant to participate in the activities since they were not aware of the teachers’ intentions of making them practise speaking. However, irrespective of the gender, medium of instruction, school, or cultural background, some students participated in the speaking activities conscious of the fact that they need to practice speech in order to learn how to speak.

The learners’ background has an important influence on their speaking comprehension. Therefore, teachers need to be aware of their students’ learning requirements, and figure out their cognitive, affective, and social needs from experience and observations as well. This can be made possible when teachers converse with students and elicit information about their background and learning goals. The teachers can also provide them with the necessary input, scaffolding and feedback, and thus derive the required assessment results (Goh & Burns, 2012).

The Learners’ Participation in the Speaking Activities

As per the survey, the learners’ experience in the classroom (shown in Figure 1) is as follows: 52.2% of the students were divided into groups for the speaking activities; for 59.8% of them, their teachers took part in the activities conducted; 71.1% understood the activities and cooperated with the teacher; 58.5% actively participated in the speaking activities and helped their classmates to participate; 67.8% learned how to speak in English from their classmates; 67.1% got equal opportunities to speak in English during the activities; 75.7% got help from the teachers when they had difficulties in communication; and for 76.5% the teacher’s attitude was positive towards them and their peers. However, some students said their teachers could not adequately appreciate their efforts to communicate in English. They were also not happy with the teachers who corrected their mistakes in front of their peers. It was also found that for 83%, their teachers corrected their mistakes and that of their peers collectively while for 16.9% the teachers corrected their mistakes and that of their peers individually; for 78.5% their teachers waited patiently for them to answer the questions asked, whereas 21.5% did not feel so. Again, as per the survey, for 76.5%, the advantage of developing speaking skills is to gain confidence in handling real-life situations, while for 22.3% it is to help them succeed at job interviews, and for 1.2% it is beneficial for higher studies. For 73.9% the greatest challenge faced while developing speaking skills was the anxiety of committing mistakes while for 26.1%, fluency was the greatest challenge. When asked for suggestions to improve the speaking activities, 65.8% said that the students should be given equal opportunities inside the classroom, 21.8% suggested that the activities should be conducted outside the classroom, 7.6% opined that opportunities should be provided to interact with their classmates, and 4.8% did not have any suggestions.

Students had varied opinions regarding the activities: some said they are curious to know new things and that they would like to take risks; others said they wish to be entertained in the language classroom; some of them wanted to have more experience of discussions; a few others wanted their teachers to share tips for success. As their expectations were different, it was not possible for teachers to group the students based on their preferences. Students had definite opinions regarding the correction of their mistakes. They requested to be corrected individually to avoid being ridiculed by their peers. There were students who needed support and they expected the teachers to find viable solutions to their problems and to adopt strategies to facilitate their oral skills. Students opined that no partiality should be shown toward certain students. For example, even if the teacher utilized some extra time talking to a few learners with problems in the class, the other students were not happy about it on the pretext that such interactions in the classroom were discouraging.

Snow (1996) stated that students learn a language effectively when they actively take part in communication activities rather than just passively accepting what the teacher says about the language. The NCLRC website, “The Essentials of Language Teaching,” advocates a balanced-activities approach to help students develop their communication efficiency in speaking. This is a combination of: (1) ‘Language input,’ (2) ‘Structured output’ and (3) ‘Communicative output.’ Language input is teacher-talk, listening and reading; Structured output is the form-focused activities; and Communicative output is the production of speech. Teachers should make students aware of the four processes that directly contribute to speech production: (1) Conceptual preparation, that is, thinking about what to say, (2) Formulation, that is, how to say it, (3) Articulation, that is, actually saying it aloud, and (4) Self-monitoring, that is, checking one’s speech for accuracy and acceptability (Levelt, 1989; Thornbury, 2005; Goh & Burns, 2012). Speakers achieve fluency when these processes are to some extent automated (Thornbury, 2005).

The Learners’ Problems with the Speaking Activities

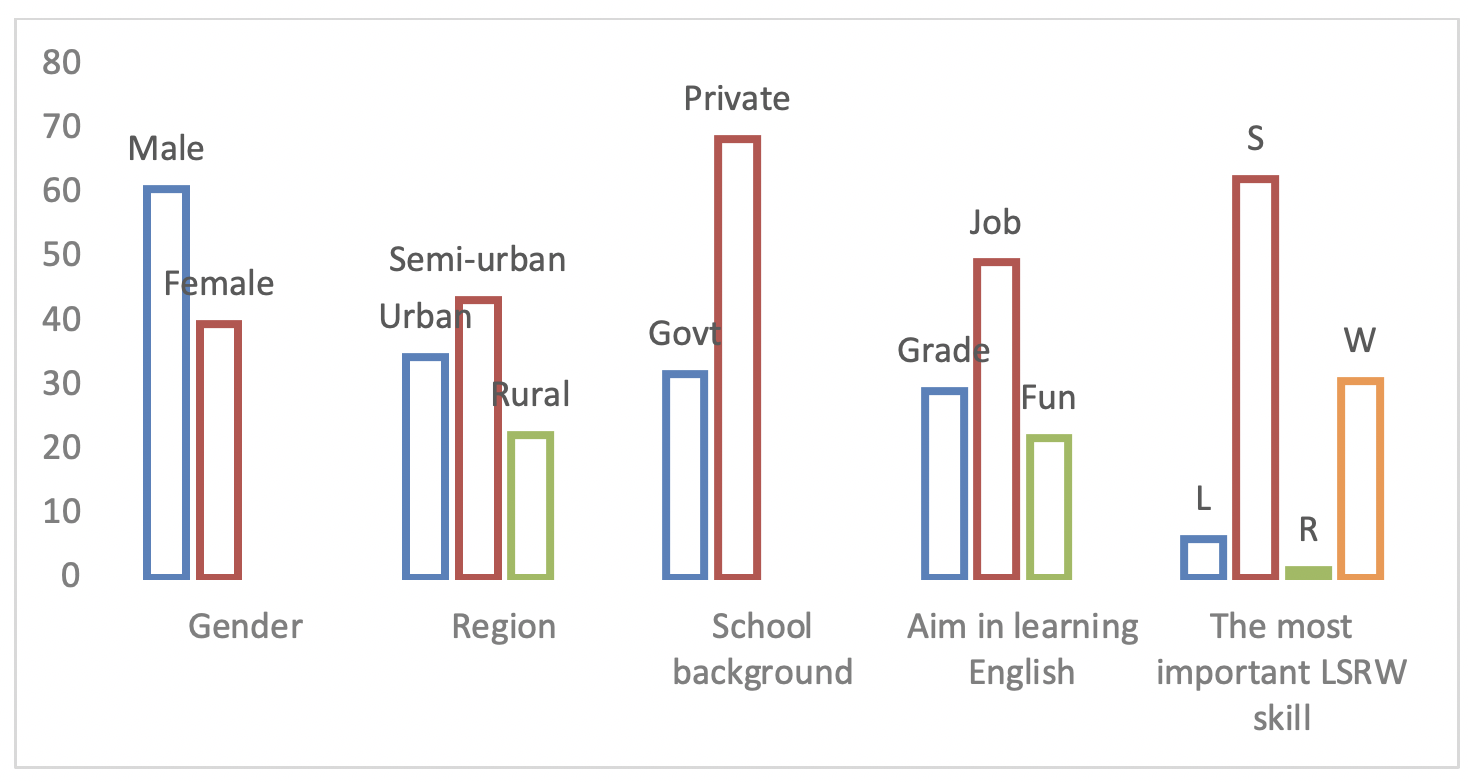

The following table indicates the speaking activities prescribed for Technical English I, Semester I:

Table 1: The speaking activities conducted in Semester I

The following is a description of the speaking activities prescribed for Technical English I, Semester I, conducted in the classroom as per the students’ survey: Data collected from the students indicate that, out of the total number of students, the following activities were not conducted for some : “Introducing oneself, one’s family/friends” for 36.69%; “Speaking about one’s place, festivals etc.” for 52.89%; “Describing a simple process” for 58.35%; “Asking and answering questions” for 57.69%; “Role play” for 52.73%; “Group interaction.” for 53.55%; “Speaking in formal situations” for 57.69%; “Responding to questions at interviews” for 58.84%; “Giving Impromptu talks” for 62.31%; and “Making presentations on given topics” for 57.69%.

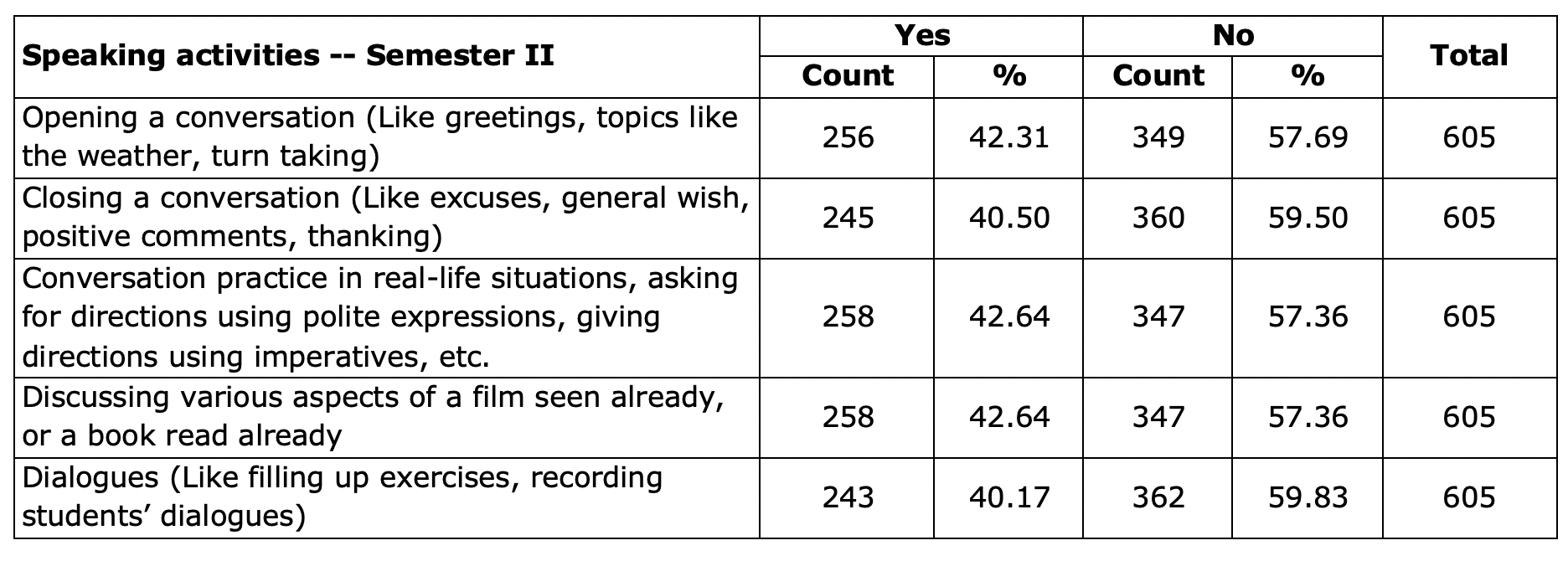

The following table indicates the speaking activities prescribed for Technical English II, Semester II:

Table 2: The speaking activities conducted in Semester II

Table 2: The speaking activities conducted in Semester II

The study indicates that the following activities were not conducted for some students: “Opening a conversation” for 57.69 %; “Closing a conversation” for 59.50%; “Conversation practices in real-life situations” and “Discussing the various aspects of a film seen already or a book read already” for 57.36%; “Dialogues” for 59.83%; Conversational skills with a sense of stress, intonation, pronunciation and meaning” for 63.31%; “Role play and mock interview for developing their interview skills” for 59.67%; “Telephonic skills” for 66.12%; “Group Discussion skills” for 63.31%; and “Different models of group discussion” for 57.02%.

In Semester I, approximately 40% said that the speaking activities were conducted while for 60% they were not. In Semester II only 40% approximately said that the speaking activities were conducted while for 60% they were not. Even when an integrated-skills syllabus is followed, speaking is neglected in the classroom because the teacher’s concentration is on the end of semester examination. Though most of the activities in the syllabus were not conducted, the students in general expressed no serious complaints against their teachers and the Technical English courses. This may be because by the time the survey was conducted, the students’ examinations were over and the results were given , and they were satisfied with their grades. It is possible that if there had been a mechanism to ensure that all the speaking activities had been used, the students’ performance level might have improved.

It is true that the teachers plan their activities on a day-to-day basis, but unfortunately some teachers do not explain the objectives behind the tasks to the students or even if they do, the students do not try to understand them. A problem identified in the daily planning of the activities is that it took too much time to group the students and get them settled for the execution of the activity. Another constraint the teacher faced was that the number of hours allocated was not sufficient for the activities prescribed. Moreover, the time allotted for each period was not enough for the performance of all the students or student groups, and so the teacher could not ensure their optimum participation. The students who did not get time to participate in the activities seemed happy when the period came to an end. Thus, the students with a weaker grounding in the target language gladly denied themselves the opportunity to develop their speaking skills. If the teacher had taken care to involve all the students in the activities, the above-mentioned issues could have been solved.

A major problem regarding the participation of many students was that they would lapse into their native tongue whenever the teacher was not around. It is also logical especially for the students from the rural background not to speak in English as they are not comfortable with the language. Even the proficient ones do not want to speak to the weak ones in English because they know they are struggling with the language. So they speak to them either in their mother tongue or broken English in a patronising manner.

Some ESL learners find it difficult to speak because of the knowledge factors and skill factors involved, and so they try to avoid taking part in the activities prescribed. According to Thornbury (2005), the difficulties the learner-speakers face can be categorized as: (1) Knowledge factors, wherein the learners are not yet aware of the aspects of the language that assist production of speech, and (2) Skills factors, wherein the learners’ knowledge is not sufficiently pre-set to guarantee fluency. Consequently, the learners may suffer from affective factors like lack of confidence or self-consciousness that might inhibit their fluency. Some teachers face the antipathy of the students who are unable to take part in the activities due to the reasons mentioned above.

The Learners’ Expectations of their Teachers and Teaching

The students in general had fewer complaints than expected about their teachers and the teaching of Technical English I and II. To put it briefly, many learners said that their expectations of the courses were met; they said they could speak in English during the activities. Most of them stated that there was a purpose behind every activity and found the speaking activities interesting and effective. However, the students felt that they should be assessed individually and given personal feedback. Though the idea sounds good in principle, the teachers struggled to find the time to pay attention to the students and assess them individually or in pairs or groups. They had an additional task of controlling the class too. Students also expected the teachers to provide them with realistic, target-oriented activities that would develop their oral skills and enable them to engage in meaningful discourses effectively.

A large number of students understood the importance of English and hoped to learn and use it in authentic contexts but they needed the scaffolding that teachers could provide. Some learners had a fear of making mistakes. Subsequently, their anxiety level increased, and they were prevented from acquiring the language input that could otherwise produce a better language output. In such cases, the students expected the teacher to create learning situations that would accommodate all of them and help them progress in their skill acquirement. There are several types of apprehensions faced by students in the classroom and trying to apply one common solution to all of them can affect the outcome.

Focus group interviews with the students

The focus group interviews were conducted with the students who participated in the survey to clarify certain points that needed further explanation for the study. The advantage of a focus group interview is that the researcher can add supplementary questions according to the ideas presented by the participants. The questions were simple, brief, and factual in the beginning while the open-ended questions were kept to the end. As already stated, five focus group interviews were held for ten students each from five colleges, with a total number of 50 students. The following are the ten questions of the Focus Group Interview and the researcher’s analysis of the responses. A sample transcript is provided in Appendix 4.

Who participates more in the speaking activities conducted in the classroom—boys or girls? Why?

In general, the girls participated more in the activities than the boys although all the students irrespective of boys or girls, understood the importance of developing their speaking skills in English. Some girls were hesitant to come forward to join in the activities and expected the teacher to compel them. On the other hand, the boys came forward without any persuasion. Often, it became an additional burden for the teacher to control their boisterous participation during the activities. The students weak in the spoken skills, irrespective of boys or girls, avoided speaking in English for fear of performing in front of their peers. As a result, they accepted the dominance of the proficient ones as a blessing in disguise.

If you consider speaking the most important skill, then what is the reason for some of you not to participate actively in the speaking activities in the classroom?

The students do not participate actively in the speaking activities for several reasons: they were unable to use the English language properly and they feared being ridiculed by their peers and looked down upon by their teachers. Naturally, they reacted in different ways: they kept quiet during the activities or they put on an attitude of indifference. Moreover, their peers interacted with them in their native tongue; and their technical subjects were taught mostly in the mother tongue. In fact, the students were conscious of the need to utilize the opportunities given to them in the English classroom because they have no other possibility of developing their speaking skills outside the English classroom. So, they requested the English teacher to persuade them to speak in English during the activities, wait patiently until they answered, and to group them with students of other parts of India who spoke different languages so that they would be forced to interact in English.

What are the advantages of developing speaking skills? Do you think that speaking activities in the classroom prepare you for efficient interactions in real-life situations?

The students expressed the advantages of developing speaking skills. They mentioned the higher status they enjoyed when they were able to speak English in the classroom in comparison with those who could not; the success that is equated with the ability to speak in English, the proficiency to get through job interviews easily, the self-reliance gained at the workplace later where they can speak and understand what others say, and also speak and make themselves understood by others. Students also agreed that speaking in English serves as the expression of their personality and adds to their confidence when they communicate with the rest of the world and meet the challenges for real-life advancement after their course of study. Therefore, they suggested that activities should be carefully planned to enable them to learn English for practical purposes in real-life situations.

Do you get enough time to practise speaking skills in the classroom? If not, would you request more time for practice?

The actual problem is not getting enough time to practise the speaking activities conducted in the classroom, but not utilizing the given time; students do not participate in the activities properly. Some of them have to use the classroom as their practice ground as they are first-generation learners who are not exposed to English outside the classroom. Unfortunately, they are reluctant to participate, therefore, the students proficient in English dominate the speaking sessions. During the interview, the weak students agreed that they are to be blamed and not their peers, teachers, the syllabus, or the methodologies. Yet, they asked the teachers to conduct more speaking activities and to encourage them to participate.

Do you have difficulties in participating in the speaking activities in the classroom? Name the difficulties you face

The students named their difficulties in participating in the speaking activities. These included being unable to interact in English and lacking the confidence to express themselves. They tended to use their mother tongue during the activities when the teacher went around the classroom to supervise the other groups. At times, the capable ones dominated or the teacher dominated giving them no chance to speak. They often developed a passive attitude and stayed in their comfort zones. They reflected that the materials used in the classroom are not related to real-life situations that would enable them to interact in English. The topics chosen are not always familiar or interesting. They lack vocabulary, grammar, fluency, pronunciation, and coherence in thought to take part in the activities.

Do you think group work can help you develop your speaking skills? How?

In general, students stated that group work could hone their speaking skills if teachers conducted enough speaking activities. For example, teachers could assist the students to overcome their inhibitions by giving equal opportunities to all the students in the group, waiting patiently for the students to utter the sentences, and/or congratulating them whenever they succeed in their attempt. Similarly, their classmates or peers could motivate them to speak out when they were shy or unable to express their ideas freely, lack content to speak, or pause or hesitate to speak. Through repetition, their confidence could be boosted. Therefore, the students requested more practice and training to participate in the group work. The students expressed the view that the teacher has to carefully monitor and ensure that the grouping is done carefully by distributing the bright ones and the weak ones evenly. According to Lightbown and Spada (1999), group work is a natural way to learn language because it creates not only a greater quantity but also a greater variety of language functions like disagreeing, hypothesizing, requesting, clarifying, and defining.

Does your teacher encourage you to participate in group activities? In what ways?

Some students agreed that the teacher encouraged them to participate in the group activity tasks. This enhanced their confidence and motivated them to perform better. Yet, they had a few complaints: they were discouraged when the teacher expected them to perform better than they were able to, when group-work became unruly, or when they were not able to respond. The students sought the teacher's special care and expertise to encourage the reserved learners who do not take risks and prefer to remain silent whether it is group work or pair work.

Ur (2005) states that teachers should motivate students to take part in conversations and try to express themselves freely. Harmer (2015) supports the teachers who make students work in pairs or groups because group work gives students ample opportunities for talking time and also controls teachers from dominating the talking time, thereby students get a chance to be more autonomous in small groups than in the whole class. Therefore, Thornbury (2005) urges teachers to convert their classes into ‘talking classrooms’ in order to develop the speaking skills of students.

Do you like your teacher correcting your mistakes? Do you think positive feedback from the teacher in the classroom would improve your speaking skills?

The students appreciated the corrections of their mistakes made by their teacher, but they opted for collective correction of their mistakes instead of individual correction in front of the whole class. That is, they wanted their teacher to make a note of the mistakes committed by all the students in general and correct them at the end of the activity instead of spotting mistakes individually during the performance. This method would protect their individuality, reduce their anxiety, and prevent them from being ridiculed by their friends. The students agreed that positive feedback from the teacher empowers them to speak while negative feedback weakens them emotionally. However, they made a distinction between negative individual feedback and negative collective feedback. Negative individual feedback is judgmental whereas negative collective feedback enables them to reflect on their mistakes and make the necessary improvement.

Are your peers helpful during classroom interactions? Do you seek help from them?

This question received mixed responses from the students. Some students admitted that their peers were very empathetic and supportive during classroom interactions. For example, if the subject given for the activity was not familiar, their peers would provide them with the content required by citing examples they can comprehend. If the topic was complex, their peers rephrased it using simple words. If they paused or hesitated in their speech, their peers prompted them with relevant words and phrases. If they could not give vent to their feelings, their peers lent a helping hand to overcome their inhibitions. If they were afraid to speak, their peers boosted their morale. However, some students felt that their peers contributed only towards a marginal growth since most of the time the activities were dominated by a group of gifted students. When asked whether they would seek help from their peers, most of them replied they would do so only from their peers whom they trusted and if they had the freedom to choose. They also pointed out the peers who ridiculed their spoken English to those who establish their superiority in some way or the other; and those who refused to talk to them just because they are very proficient in English.

Do you attempt to speak in English outside the classroom? Are you successful in your attempts?

Most of the students interviewed do not speak in English outside the classroom. To make matters worse, such students are also discouraged by other weak students from attempting to speak in English, arguing that using English outside the classroom is artificial. These students believe that speaking in the native language is a way of gaining popularity and acceptance among their peers. A few students who are proficient in English admitted that they make use of the opportunities outside the classroom to speak in English and that they are successful in their attempt. But most students suggested a constructive atmosphere like club activities and participation in symposiums where they could develop a positive attitude and be able to speak in English successfully outside the classroom.

Recommendations by the Teacher-researchers

The following are some of the recommendations derived by the teacher-researchers from the Students’ Survey and the Focus Group Interviews.

As stated above, it is the teacher’s responsibility to make the students aware of the characteristics of the spoken language and its differences from written language, so that they can be more confident. Teachers should design activities to make them aware of the functions of speech such as interaction, transaction, and performance (Richards, 2008). Basturkmen (2016) recommends course designers determine the types of interactive speaking events that their learners will encounter in their target situation, and design materials using authentic interactions in the context. She reminds teachers of the need for scaffolding during dialogic interactions. Bailey and Nunan (2005) offer some key principles in teaching speaking: Be aware of the difference between EFL and ESL learners, help students practice both fluency and accuracy, give students opportunities to talk through pair work and group work, plan speaking tasks that involves the negotiation of meaning, and design speaking tasks that provide guidance and practice in transactional and interactional speaking. Nation and Newton (2009) help teachers design activities based on four strands: meaning focused input, meaning focused output, language focused learning, and fluency development. Therefore, teachers need to choose activities to help students to understand the modern objectives and use them further to develop their skills. The speaking activity materials should be familiar and interesting to enable the students to practise English in real-life situations.

Training should be given to students to speak in English during the group activities, and they should be congratulated whenever they succeed in their attempt. Zhang et al. (2020) assert that in order to reduce the anxiety levels of the students positively, the teacher should build a supportive and cooperative atmosphere rather than a competitive or stressful one. Equal opportunities should be given to students to speak in a group, and the capable ones should be discouraged from dominating the weak, because it demotivates them. A fair distribution of mixed-ability students in a group can enhance participation within the group. Noisy and unruly participation should be properly directed and controlled tactfully without hurting the students’ feelings (John, 2017).

The students’ mistakes should be corrected collectively at the end of the group performance, and not individually during the performance in front of the whole class. Positive guidelines for improvement should be given to students because positive feedback empowers them to speak. On the other hand, negative judgmental feedback should be avoided because it weakens them emotionally. Zhang et al. (2020) recommend teachers provide personalized feedback and create multiple presentation opportunities for better performance.

Explicit training instructions and practice should be given to students to speak in academic speech events in the classroom. Examples are monologues, such as conference presentations and undergraduate talks, dialogues like seminars, class discussion, poster presentations and oral examination (Charles & Pecorari, 2016). Specific learning objectives should be identified with speaking and students should be trained in the sub-skills of speaking (Anthony, 2018). Practice in interview skills and question-answer sessions should be given to train students to tackle questions during their job interviews. Opportunities for participation in club activities should be provided to assist speaking outside the classroom.

The syllabus should be reappraised periodically to include newer topics in speaking like team meetings, video conferences, etc. There could be a mechanism to ensure that the speaking activities prescribed are conducted in the classroom. The hours allotted in the syllabus are not sufficient to conduct all the activities prescribed, so the University could introduce more hours for speaking. According to Basturkmen (2010), an ESP course requires a narrowing down of language and skills that are to be taught. If proficiency in speaking skills is a need for students, then an ESP speaking course should be designed with the help of experts, and the course should consider the wide range of ESP speaking contexts (Feak, 2013). Woodrow (2018) provides guidelines to ESP practitioners on the different approaches to course design. Formative and summative assessment of the students’ oral performance should be done to ensure that speaking is taught in the classroom (John, 2017)

Conclusion

The outside world is moving fast at an incredible speed in every sphere including the use of language, and students are expected to flow along with the current and face authentic situations. They also need to use the appropriate vocabulary, idioms, and the nuances of the language required for situations. If language classes are to catch up with the change, teachers have to put in their best efforts for the change.

Speaking is often neglected in integrated-skills approach syllabi and the focus of teachers is on writing skills. According to the students’ survey examined here, approximately 40% of the speaking activities prescribed in the syllabi of Technical English I and II were conducted in both the semesters. The common problems identified among the students while learning the language were: low proficiency in the language, lack of knowledge of the subject, making grammatical mistakes; anxiety to be accepted by others, being judged as weak in oral communication by their peers, and coming out of their comfort zones. Moreover, weak learners are discouraged from speaking by their friends who do not want them to use a language in which not all of them are adept. There is also a tendency among students who are proficient in English not to speak in English to those who struggle to communicate in that language. Instead, they talk to them in the native language or if they cannot speak the native tongue, they speak to them in broken English in a patronizing manner. The students felt that the inequality in the classroom due to the disparity in the spoken skills should be taken care of, and a relaxed environment should be created that would be congenial to the enhancement of their speaking skills. They count on the classroom as a place that can offer them opportunities to develop their vocabulary, apply their knowledge of grammar, and develop their speaking style and fluency. The weak students expect to break through this attitude. They expect that their teachers understand their strengths, weaknesses, individual learning goals at the personal level, and prescribe individual learning solutions that would help them to be fluent and self-assured. They want their teachers to be patient, empathetic, and friendly. The study concludes with recommendations to make the teaching of speaking skills more effective and suggests a speaking-specific course for the same.

References

Anthony, L. (2018). Introducing English for Specific Purposes. Routledge.

Arnó-Macià, E., Aguilar-Pérez, M., & Tatzl, D. (2020). Engineering students' perceptions of the role of ESP courses in internationalized universities. English for Specific Purposes, 58, 58-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2019.12.001

Bailey, K. M., & Nunan, D. (2005). Practical English language teaching: Speaking. McGraw-Hill.

Basturkmen, H. (2010). Developing Courses in English for Specific Purposes. Springer.

Basturkmen, H. (2016). Dialogic interaction. In K. Hyland & P. Shaw (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of English for Academic Purposes (pp. 152-164). Routledge.

Biber, D. (2006). University language: A corpus-based study of spoken and written registers. Benjamins.

Brown, G. & Yule, G. (1983). Teaching the Spoken Language. Cambridge University Press.

Bygate, M. (1987). Speaking. Oxford University Press.

Byrne, D. (1986). Teaching oral English. Longman.

Charles, M., & Pecorari, D. (2016). Introducing English for Academic Purposes. Routledge.

Dudley-Evans, T., & St John, M. J. (1998). Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A multi-disciplinary approach. Cambridge University Press.

Feak, C. B. (2013). ESP and Speaking. In Paltridge, B. & Starfield, S. (Eds.). The handbook of English for specific purposes. Wiley-Blackwell.

Gaffas, Z. M. (2019). Students’ perceptions of the impact of EGP and ESP courses on their English language development: Voices from Saudi Arabia. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 42, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.100797

Goh, C. C. M., & Burns, A. (2012). Teaching speaking: A holistic approach. Cambridge University Press.

Harmer, J. (2015). The Practice of English Language Teaching (5th ed.). Pearson.

Hutchinson, T., & Waters, A. (1987). English for specific purposes. Cambridge University Press.

Hyland, K. (2006). English for academic purposes: An advanced resource book. Routledge.

Hyland, K., & Wong, L. L. C. (Eds.). (2019). Specialised English: New directions in ESP and EAP research and practice. Routledge.

John, D. (2017). Employing group work to foster speaking skills: A study of success and failure in the classroom. MEXTESOL Journal, 41(3), 1-9. http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=2521

Jordan, R. R. (1997). English for academic purposes: A guide and resource book for teachers. Cambridge University Press.

Kennedy, D. (n.d.). The Essentials of Language Teaching: Guidelines for building communicative competence. Key Words. https://essentialsoflanguageteachingnet.wordpress.com

Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. MIT Press.

Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. (1999). How languages are learned. Oxford University Press.

Lockwood, J. (2019). What do we mean by ‘Workplace English’? A syllabus framework for course design and assessment. In Hyland, K., & Wong, L. C. (Eds.). Specialised English: New directions in ESP and EAP research and practice. Routledge.

Luoma, S. (2004). Assessing Speaking. Cambridge University Press.

Mauranen, A. (2019). Academically speaking: English as the Lingua Franca. In Hyland, K., & Wong, L. C. (Eds.). Specialised English: New directions in ESP and EAP research and practice. Routledge

Nation, I. S. P., & Newton, J. (2008). Teaching ESL/EFL listening and speaking. Routledge.

Richards, J. (2008). Teaching speaking and listening. Cambridge University Press.

Snow, D. B. (1996). More than a native speaker An introduction for volunteers teaching English abroad. TESOL Inc.

Sun, Y. (2016, 22 April). 9 strategies for 21st-Century ELT professionals. TESOL Blog. http://blog.tesol.org/9-strategies-for-21st-century-elt--professionals

Thornbury, S. (2005). How to Teach Speaking. Pearson.

Ur, P. (2005). Discussion that Work: Task-centered fluency practice. Cambridge University Press.

Woodrow, L. (2018). Introducing course design in English for specific purposes. Routledge.

Zhang, X., Ardasheva, Y., & Austin, B. W. (2020). Self-efficacy and English public speaking performance: A mixed method approach. English for Specific Purposes, 59, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2020.02.001